In June 2017, Alex Honnold was the first climber to free solo El Capitan. For many people, this statement has no relevance; to be honest, I didn’t fully grasp the significance the first time I heard it. Listening to an interview with Alex Honnold, I began to understand what that first sentence actually means – Alex Honnold climbed a 3,000 foot sheer rock face in Yosemite without ropes – and lived to claim the record for doing so.

Intrigued to learn more about Honnold, I went down the Google rabbit hole and ultimately read his book. Not only did he free solo El Capitan, he has many records on some of the most challenging climbs in the world. Looking at images of Alex hanging off rocks by his fingers or standing on thin ledges with the clouds below him admittedly makes my heart rate quicken. How on earth did he maintain a rational emotional state to accomplish these feats? I was not the first person to ask this – he apparently gets this question a lot.

In an account of Honnold’s epic climb, his relationship with fear is described: “Honnold sees [fear] in more pragmatic terms. ‘With free-soloing, obviously I know that I’m in danger, but feeling fearful while I’m up there is not helping me in any way,’ he said. ‘It’s only hindering my performance, so I just set it aside and leave it be.’” He acknowledges and accepts death. He is able to stay present in the moment, even if that moment is thousands of feet high hanging on by the tension of his hands and feet.

Honnold’s preparation for a climb like this is of note – he researches extensively, keeps notes and reflects on his climbs. Does this constant immersion in his physical exploits help train his mind for when he’s actively climbing and needs to mentally stay in the moment? Possibly. There is a growing recognition for the value of taking a few minutes each day to journal as a way to develop mindfulness (which can help regulate emotional responses) and work towards goals.

Psychologist Susan David, PhD. discusses in her Ted Talk the value of pushing past the emotional comfort zone in order to become a more effective and successful version of ourselves. She reasons that emotions are data, but not directives. While we need to embrace all emotions (both “good” and “bad”), we should not use our emotions alone to make decisions about how to act.

While we may not all be able to regulate our fear response like Alex Honnold, we can take a page from his book on how he sorts consequence and risk:

“…Alex inclines toward a hyperrational take on life. He actually insists, ‘I don’t like risk. I don’t like passing over double yellow. I don’t like rolling the dice.’ He distinguishes between consequences and risk. Obviously, the consequences of a fall while free soloing are ultimate ones. But that doesn’t mean, he argues, that he’s taking ultimate risks. As he puts it, ‘I always call risk the likelihood of actually falling off. The consequence is what will happen if you do. So I try to keep my soloing low-risk – as in, I’m not likely to fall off, even though there’d be really high consequences if I did.’”

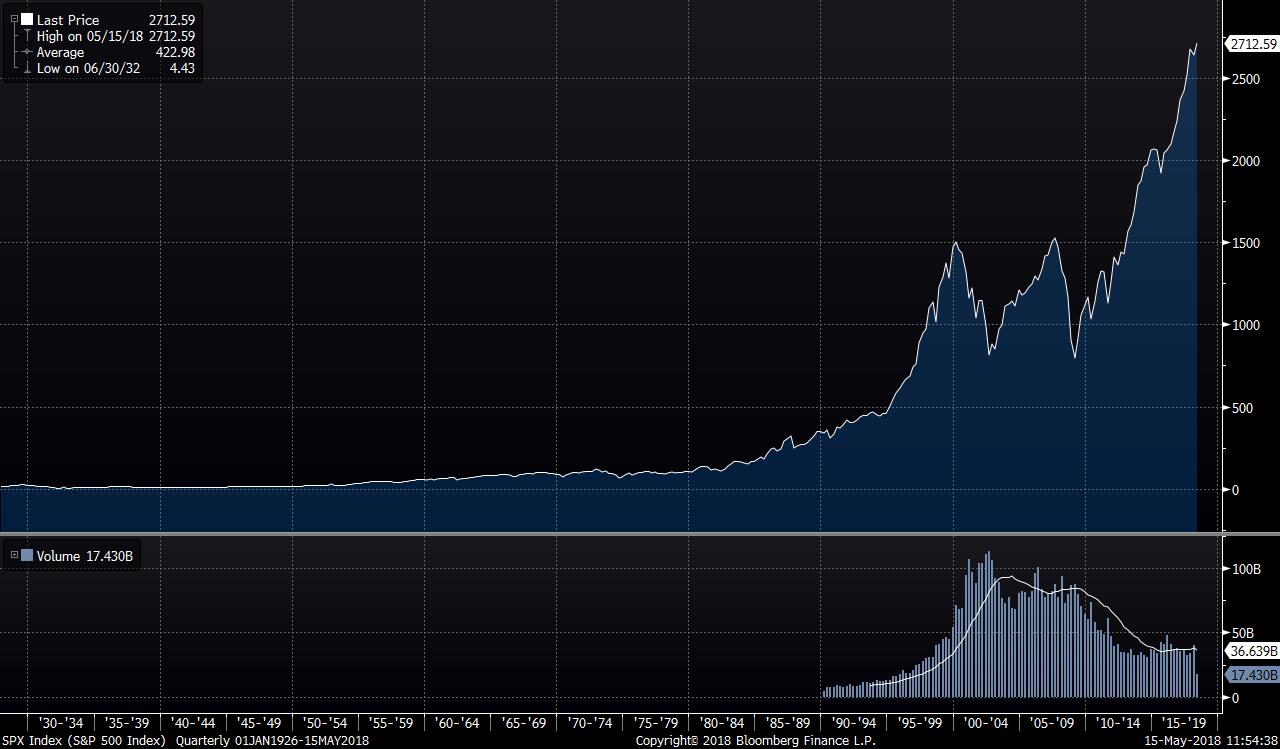

I think this approach to risk versus consequence is relevant to long term investing. In reality, the market has generally gone up over time.

Since 1929, the 31 corrections of -10%+ have accounted for less than a quarter of the total days during bull markets. These corrections have averaged 100 days – less than 3 months – in duration.

If an investor does the due diligence to identify a manager with whom they align on approach and objective, and puts their money into a strategy that is long-term oriented with a track record to back it up, isn’t staying invested over the long term a low-risk strategy? The consequence of selling at the wrong time can be significant – so instead of focusing on timing the market, it has been shown to be better to take the low risk approach to just maintain the investment. (Bill Miller and Charles Ellis agree on this).

Investing can be a particularly tricky endeavor, as so much emotion is tied up in the effort. Since the only certainty is that the future is uncertain, investors are inherently putting themselves in a state where future emotions are unknowable. Susan David explains that our culture puts too much emphasis on the positive emotions – it’s unsustainable to be positive 100% of the time. That’s true for investors. It’s unreasonable to think that you’re going to be happy 100% of the time with the market. The challenge is to recognize the emotions during periods of volatility or uncertainty and sort out which ones are relevant data points to the objective. Combining those with action are what can push you into the next level.